Compartment syndrome is an extremely painful condition that, if presenting acutely, is a medical emergency. Left untreated, it can result in serious consequences such as ischaemia, necrosis, amputation of the affected limb or even death (Torlincasi et al. 2023; Cleveland Clinic 2023).

Note: This Article will focus on the acute form of compartment syndrome.

What is Compartment Syndrome?

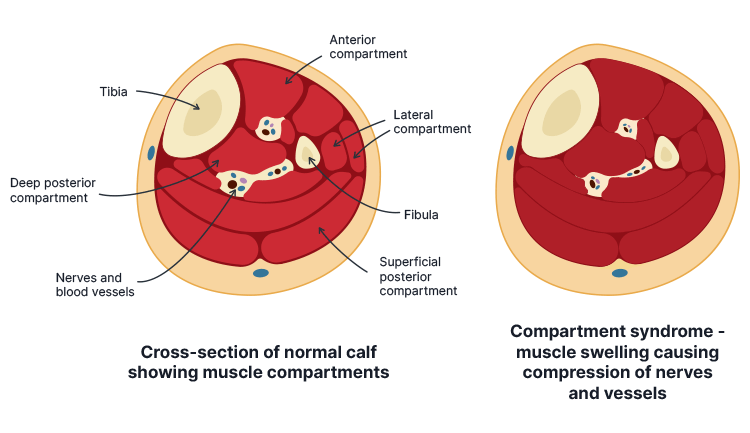

The arms and legs are divided into several segments known as fascial compartments. Each compartment comprises a group of muscle tissue, blood vessels and nerves contained within a strong membrane known as the fascia (Cleveland Clinic 2023).

The fascia is inelastic, preventing the compartments from rapidly expanding. Compartment syndrome occurs when blood or fluid accumulates in the intracompartmental space, and the compartment is unable to stretch to accommodate this increased fluid volume. This causes a high level of pressure, which in turn impedes perfusion to the affected area (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

Compartment syndrome most commonly occurs in the anterior compartment of the leg, but can also affect the forearm, thigh, buttock, shoulder, hand, foot or abdomen (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

There are two types of compartment syndrome: acute and chronic.

- Acute compartment syndrome is typically associated with trauma and has a sudden onset. It’s a medical emergency that can result in significant disability or even death.

- Chronic compartment syndrome is usually less serious and develops gradually, during or after intense physical exertion (e.g. exercise).

(Cleveland Clinic 2023; NHS 2023)

What Causes Acute Compartment Syndrome?

Potential causes of acute compartment syndrome include:

- Bone fracture (most commonly a long bone fracture)

- Surgery (e.g. orthopaedic, nerve or vascular procedure)

- Traumatic injury (e.g. crush injury, penetrating trauma)

- High-pressure injection injury

- Constrictive bandage or plaster cast

- Animal bite or sting

- Severe burn

- Severe bruising

- Recreational drug injection

- Haematologic cause (e.g. reperfusion injury, thrombosis, bleeding disorders, vascular disease, spontaneous haemorrhage)

- Anticoagulation

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Intravenous fluid (fluid extravasation or massive fluid resuscitation, e.g. due to sepsis or a severe burn)

- Prolonged compression of a limb (e.g. due to poor surgical positioning or drug or alcohol intoxication)

- Revascularisation procedure (e.g. extremity bypass surgery, embolectomy, thrombolysis)

- Group A streptococcus infection of a muscle.

(Hammerberg 2025; Healthdirect 2024; ACI 2018; Torlincasi et al. 2023; Cleveland Clinic 2023)

Rarely, acute compartment syndrome can present without any signs of injury (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

Risk Factors for Acute Compartment Syndrome

Those at increased risk of compartment syndrome include:

- Males under the age of 35 (possibly due to having a larger relative intracompartmental muscle mass and being at greater risk of sustaining a traumatic injury)

- Children with paediatric leukaemia (some children with this condition have experienced acute compartment syndrome without sustaining any trauma)

- People with bleeding disorders, including haemophilia

- People at increased risk of bleeding, including those:

- Taking anticoagulants

- With a family history of major bleeding

- With a low platelet count

- With severe liver or kidney disease.

(Torlincasi et al. 2023; ACI 2018)

Symptoms of Acute Compartment Syndrome

The onset of symptoms is typically within a few hours after sustaining trauma. However, in some cases, symptoms can develop up to 48 hours later (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

A patient with compartment syndrome may present with:

- A tense, wood-like feeling in the affected compartment

- Severe pain disproportionate to the injury (may be described as a burning sensation or a deep ache), which is exacerbated by passive stretching of the affected area and cannot be alleviated with analgesia

- Paraesthesia

- Pallor caused by vascular insufficiency (uncommon symptom)

- Muscle weakness

- Reduced sensation in the affected area

- Paralysis (typically a later symptom).

(Torlincasi et al. 2023; Hammerberg 2025)

Diagnosing Acute Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is typically identified via clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and risk factors, as prompt treatment is crucial (Torlincasi et al. 2023; TeachMe Surgery 2022).

Physical examination should involve:

- Assessing the skin for lesions, swelling or discolouration

- Palpating the compartment to assess temperature, tension and tenderness

- Checking the patient’s pulse

- A two-point discrimination test, which is used to assess whether the patient can identify that two objects touching the skin close together are separate objects rather than one

- Assessing motor function.

(Torlincasi et al. 2023; Physiopedia 2025)

Traditionally, compartment syndrome was diagnosed using ‘the five Ps’: pain, pulselessness, paraesthesia, pallor and poikilothermia (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

However, the five Ps are now considered clinically unreliable, as aside from pain, they may only occur in the later stages of compartment syndrome by the time irreversible tissue damage has already occurred (Rasul Jr 2024; Hammerberg 2025).

The most reliable diagnostic method for compartment syndrome is measuring the intracompartmental pressure (ICP) of the affected area using a manometer or slit catheter. While this is not a necessary test, it can assist in confirming a diagnosis if uncertainty exists (Torlincasi et al. 2023; TeachMe Surgery 2022).

An ICP of over 30 mmHg indicates compartment syndrome (normal pressure is between 0 mmHg and 8 mmHg) (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

Other diagnostic tests that might be used include:

- Radiograph, if the patient has a suspected fracture

- Doppler ultrasound to assess for occlusion or thrombus

- Creatine kinase (CK) blood test (elevated CK levels are indicative of compartment syndrome)

- Complete blood count and coagulation studies (preoperatively).

(Torlincasi et al. 2023; TeachMe Surgery 2022)

Note: Due to the severity of the condition and the potential for limb loss, treatment should be prioritised with less time spent on confirming the diagnosis (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

Treating Acute Compartment Syndrome

Once compartment syndrome is suspected, management steps might include:

- Ensuring the affected limb is at a neutral level (not elevated or lowered)

- Administering supplemental oxygen

- Removing restrictive casts, dressings, or bandages from the affected limb

- Preventing hypotension ad administering blood pressure support if necessary

- Administering analgesia intravenously.

(Torlincasi et al. 2023; TeachMe Surgery 2022)

Compartment syndrome is treated using a surgical procedure known as a fasciotomy, wherein the skin is cut down to the fascia to release the accumulated pressure. The incision is then left open for several days to prevent the intracompartmental pressure from increasing again before being closed (ACI 2018).

Whether or not a fasciotomy is indicated generally depends on the ICP in the affected compartment and the amount of time that has elapsed since the trauma occurred, as if the injury is left untreated for too long, irreversible damage may have already occurred (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

If necrosis has already occurred before a fasciotomy can be performed, an infection may be present. This may require debridement or even amputation to prevent systemic spread (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

The sooner a fasciotomy is performed, the more likely the patient is to recover their limb function. If left untreated for too long, the patient may experience residual nerve damage (Torlincasi et al. 2023).

Postoperative Care

Postoperative care might involve:

- Physical therapy to help the patient restore function and strength in the affected limb, as well as prevent contractures and stiffness

- Wound care and monitoring

- An antibiotic regimen, if an infection is present

- Analgesia

- Use of an ambulatory device (e.g. crutches) while the injury is healing

- Occupational therapy.

(Torlincasi et al. 2023)

Complications of Compartment Syndrome

Potential complications of compartment syndrome and fasciotomy include:

- Cosmetic defects in the affected area

- Recurrent compartment syndrome due to scarring

- Pain

- Contractures

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Nerve damage, which may lead to numbness and/or weakness

- Infection

- Acute renal failure

- Death (usually occurs due to infection that leads to sepsis and multiorgan failure).

(Torlincasi et al. 2023)

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Where in the body does compartment syndrome most commonly occur?

Topics

References

- Agency for Clinical Innovation 2018, Acute Compartment Syndrome, New South Wales Government, viewed 27 June 2025, https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/458188/ACI-MSK-Acute-compartment-syndrome.pdf

- Cleveland Clinic 2021, Compartment Syndrome, Cleveland Clinic, viewed 27 June 2025, https://teachmesurgery.com/orthopaedic/principles/compartment-syndrome/

- Hammerberg, EM 2025, Acute Compartment Syndrome of the Extremities, UpToDate, viewed 27 June 2025, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-compartment-syndrome-of-the-extremities

- Healthdirect 2024, Compartment Syndrome, Australian Government, viewed 27 June 2025, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/compartment-syndrome

- National Health Service 2023, Compartment Syndrome, NHS, viewed 27 June 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/compartment-syndrome/

- Physiopedia 2025, Weber Two-Point Discrimination Test, Physiopedia, viewed 27 June 2025, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Weber_Two-Point_Discrimination_Test

- Rasul Jr, AT 2020, Acute Compartment Syndrome, Medscape, viewed 27 June 2025, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/307668-overview

- TeachMe Surgery 2022, Compartment Syndrome, TeachMe Surgery, viewed 27 June 2025, https://teachmesurgery.com/orthopaedic/principles/compartment-syndrome/

- Torlincasi, AM, Lopez, RA & Waseem, M 2023, ‘Acute Compartment Syndrome’, StatPearls, viewed 27 June 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448124/

New

New